Yesterday I began this piece with these words: “This post is already the most painful one I’ve written to date. Starting to type as my eyes well with tears is not typical.” Today, I started over. Because this blog is not about tears or despair but hope. Today, this post is about overcoming fear by finding, holding onto, and building on, hope.

Yesterday was far from a typical day in the United States: student-focused, and led, ‘March for our Lives‘ anti-gun violence demonstrations and marches took place across the country  as well as further afield (e.g. London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, and Sydney).

as well as further afield (e.g. London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, and Sydney).

You very likely know that already. Maybe, like Bob and I, you were one of the hundreds of thousands that took part, listening to powerful, heartfelt, hope-filled speeches. Maybe you were even one of those who stood up and told your story of fear?

What brought me to tears as my feet went numb with the cold, and later in my dining room, was the knock-between-the-eyes visual image of so many American children living their lives in fear. Add to that, the realization that so many of those same kids are still hanging onto hope.

At home after the march, I asked Bob if he’d ever experienced a time of living in fear. He hadn’t. I thought about my times of on-going fear; the times I’d originally thought would form the basis of a post about overcoming fear. The long string of nights my mind, more than reality, had me lying awake watching the locked doorknob of my bedroom—waiting for it to turn. I planned to share how I’d finally used logic to overcome past fears that were distorting my present.

That logic went like this:

- I lived in New Zealand, a country of relatively little crime.

- I lived in a suburb of the capital, that was even less prone to crime than other areas.

- I lived at the end of a winding, tree-lined path above a winding, tree-lined road.

- Of course, it was possible someone might appear in my doorway, but the odds were extremely remote.

Facts broke my fear.

At other times, by virtue of being female, my fears were grounded in reality, supported by facts and by firsthand experience. Yesterday, at least one speaker in Chicago acknowledged being female means greater risk, greater fear, than for men. That was not the focus of the day, however, nor will it be for me—that will be a later post.

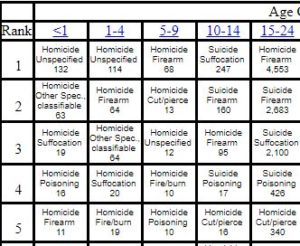

10 Leading Causes of Violence-Related Injury Deaths, United States

2016, All Races, Both Sexes

When facts support fear as an everyday reality, when children can cite firsthand experiences of seeing a friend shot and killed in front of them, how do they overcome that? I’m not a psychologist, nor a Pollyanna. I only know strong bonds with family, friends, and others would be critical after such a trauma. Beyond that, how much does anyone get over seeing a loved one killed? Without support … is simply remaining alive from one day to the next, hoping to bury, or maybe to overcome their emotional wounds when they’re older, the best these children and teens can expect? As a nation, is that the best we can offer? This CDC chart to the left could lead anyone to despair. Imagine being one of the infants, toddlers, teens, or young adults represented by these numbers. Imagine being their sibling, mom, or dad. Grandparent. Best friend.

Here comes the hope.

Beside me on the couch, Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment NOW: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018) lies open to the inside cover and the first question the book asks: Is the world really falling apart? By way of answering, Pinker presents evidence that:

“…life, health, prosperity, safety, peace, knowledge, and happiness are on the rise,

not just in the West but worldwide.”

For the school kids who feel unsafe in their classrooms or neighborhoods, stats like these do nothing to reduce their fear. For those of us “living” their terrifying reality secondhand, through speeches or news articles, Pinker’s findings are important. By keeping perspective, pushing for realistic, fact-based solutions, and refusing to become fatalistic, we can help bring about change for those kids.

Pinker cites a massive study of studies—2,300 to be precise—that evaluated past attempts to reduce violent crime. It concluded:

“… the single most effective tactic for reducing violent crime is focused deterrence.”

Pinker explains (page 174) this means:

- a “laser-like” neighborhood focus to identify the hot spots and rising dangers,

- delivering a simple, concrete message to the individuals and gangs behind the threats: “stop shooting and we will help you, keep shooting and we will put you in prison.”

- the cooperation of the trouble-makers’ full community as well as their relatives to get this message across and to enforce it.

Remember “focused deterrence” arose as the best solution out of 2,300 studies. The inclusion of relatives and the community as integral to the solution, and the personal, compassionate nature of “stop shooting and we will help you” brings me real hope for two key reasons:

- Communities are not expected to wait till poverty or other deep-seated issues are eradicated. In fact, Pinker boldly states (page 173): “Forget root causes. Stay close to the symptoms …”

- There’s actual evidence compassion towards individuals works.

In 2016, NPR’s fabulous Invisiblia program described how two Danish policemen applied compassion as an “unusually successful” method for combating radicalization of young Muslim men in their town. Derided by some in the media, the cops described their approach (of welcoming home, mentoring, and providing the men support to find work and housing), as “an entirely practical decision designed to keep their city safe.”

The program achieved more than that. By ‘flipping the script,’ (showing compassion when harshness would be expected) the Arhaus model allowed the marginalized men to let down their guard, to consider they might have been wrong about the society they’d rejected, maybe rather than an enemy it could be a place where they could belong. This script flip, apparently has a name: non-complementary behavior. Essentially, it’s doing the unexpected: acting warmly to someone who treats you with hostility. While not a natural way of reacting, it’s said to be “a proven way to shake up the dynamic and produce a different outcome from the usual one,” as a Washington D.C. dinner party found when an uninvited visitor showed up.

Another 2016 NPR episode of Invisiblia told how increased vulnerability actually led to increased safety and productivity. On a deepwater oil well. With plans to build a 48 story tall offshore platform in 1997, Shell Oil knew safety would be a priority issue. An external consultant nailed the real problem: fear … “how the men dealt with their feelings.” Putting tough-as-nails oil-rig workers through intensive workshops to open them up to themselves, their families and each other, enabled the men to admit to mistakes or lack of understanding, to ask for help, and to be open to learning. All of which led to better working and interpersonal relationships. In 2008, Harvard Business Review published an analysis of the outcome, concluding:

“The problem lies not in traditionally masculine attributes per se—many tasks require aggressiveness, strength, or emotional detachment—but in men’s efforts to prove themselves on these dimensions, whether in the hazardous setting of an offshore oil platform or in the posh, protected surroundings of the executive suite.”

When cracking the hardest nuts—empowering them to be fully and vulnerably human—brings about positive results for all concerned, when community involvement and compassion lead to safer environments, when clear and proven action plans exist and don’t require overcoming complex issues before getting started … all this, to me, spells hope.

Hope in itself doesn’t overcome fear. They can live side by side, but by finding, holding onto, and building on hope, we can bring about real change and we can overcome fear.

Apologies that this post reads more like a research paper rather than a personal journey. I needed to hunt for things to base my hope on. If you have personal journey stories you’re willing to share, I warmly invite you to do that. Remember you can always omit your, and other people’s, names for the sake of privacy.